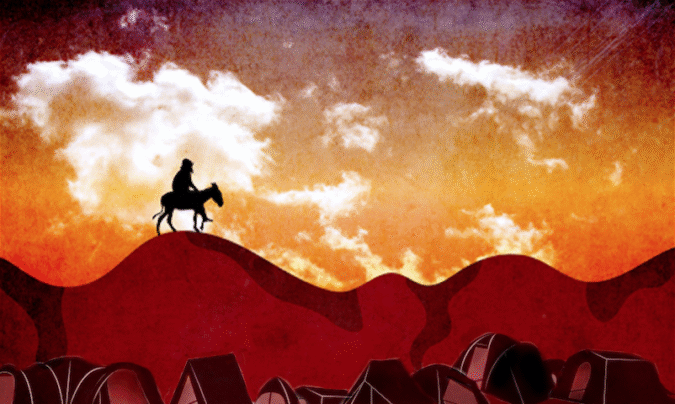

Rabbi Becky Silverstein: Matot-Masei Mapping Our Stories in Fits and Starts

Rabbi Silverstein writes about journeys – physical and spiritual. This parashah names 40 years of journeying by listing 42 different sites, but without much narrative. It is up to the reader to provide the story and the message. For instance, she cites the Kedushat Levi, who wrote that the Israelites stayed longer in some places because it took longer to find the holiness of the site